Codes of Conduct are a set of rules and recommendations that can be adopted by companies, national and international organisations, private groups, etc. They seek to guide the behaviour of their members by establishing ideals and values, describing what is considered moral, ethical, and honourable, offering recommendations and support in the face of sensitive situations, and providing channels for communicating abuse. Their aim is to deter corruption and contribute to a more ethical environment.

What are Codes of Conduct?

Codes of conduct in the defence and security sectors build on the specific corporate culture of the military and other security establishments. They consist of a series of directives, rules, and regulations describing what is considered as ethical behaviour of personnel, what to do when faced with a delicate situation that may result in corruption, and how to report corrupt actions of others. Codes of conduct, usually, consist of a list of articles. Although they can vary from country to country, the most common topics are:

- General principles

- Lawful Duties of the public officials/civil and military personnel/members

- Ethical use of their powers

- Conflicts of interest

- Disclosure of assets and transparency

- Acceptance of Gifts

- Bribery

- Accountability

- Confidential Information

- Conflicting professional/business/political activities

- Reporting

- Activities/employment after leaving public service

Codes of conduct can be adopted at an organisational, national and/or international level. Corruption often bypasses national borders. Therefore, channels for international cooperation on these matters should be established. Codes of conduct, along with other regulations, represent a perfect opportunity for that. They can insist on the importance of transparency, reporting and international legal cooperation.

A few valuable examples:

OSCE Code of Conduct on Politico- Military Aspects of Security is a Code of Conduct applied on an international level. In the setting of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe, it outlines the duties and guiding principles of its member and participating states.

OSCE Code of Conduct on Politico- Military Aspects of Security is a Code of Conduct applied on an international level. In the setting of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe, it outlines the duties and guiding principles of its member and participating states.

Another Example of an international Code of Conduct is the UN International Code of Conduct for Public Officials. This code’s brief and structured outline can serve as foundation for developing other codes of conduct that are adapted to a particular context.

Another Example of an international Code of Conduct is the UN International Code of Conduct for Public Officials. This code’s brief and structured outline can serve as foundation for developing other codes of conduct that are adapted to a particular context.

The Model Code of Conduct for Public Officials, developed by the Council of Europe in its Recommendation No. R. (2000) 10 can serve the same purpose.

The Model Code of Conduct for Public Officials, developed by the Council of Europe in its Recommendation No. R. (2000) 10 can serve the same purpose.

Additionally, OECD has issued a Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions, which constitutes a crucial reference document when it comes to codes of conduct in the sphere of resource management in defence.

Additionally, OECD has issued a Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions, which constitutes a crucial reference document when it comes to codes of conduct in the sphere of resource management in defence.

Finally, a great national example is the Norwegian Code of conduct: Ethical Guidelines for Contact with Business and Industry in the Defence Sector. Published in 2011, it is a short, clear-cut text, well-illustrated and easy to read.

Finally, a great national example is the Norwegian Code of conduct: Ethical Guidelines for Contact with Business and Industry in the Defence Sector. Published in 2011, it is a short, clear-cut text, well-illustrated and easy to read.

Why are they important?

Codes of Conduct and other voluntary guidelines make a real difference in the security-sector institutions because the majority of military and other serving personnel take great pride in serving their nation and the security sector establishment. Honouring the ideal of such an establishment is part of the military culture.[1]

Although some are less evident than others, the forms of corruption are many. In order to avoid confusion and omission, there should be a clear statement on what is expected from personnel, what is and is not acceptable, and how to avoid and deal with conflicting situations. This should be supported by a global adherence to the established standards of behaviour. Senior officers and officials set the example by promoting codes of conduct as the central component the security sector establishment.

How do they work?

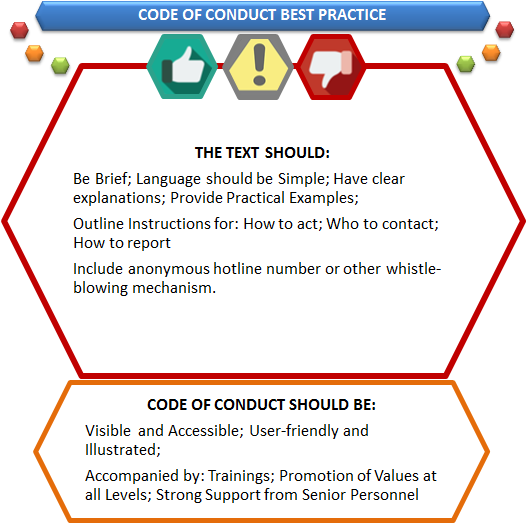

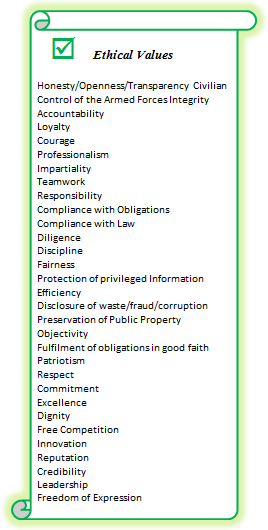

According to Transparency International (TI), the ideal guidance framework for defence officials and members of the armed forces is comprised of three core components: a legal framework with its ethical guidance, the code of conduct, and a statement of values. The legal framework is composed of an array of legal statutes, civil service acts, and disciplinary and penal codes. Since these documents are often written in a technical language, they should be accompanied by guidance notes for better understanding. The code of conduct is a set of behavioural norms and common values. It should be clear, brief and accessible to all members of the security sector establishment. The statement of values is an independent, distinct declaration which articulates an organisation’s overarching ethical principles and compliments the code of conduct. It should be widely distributed and promoted by senior officials.[2]

The effectiveness of these documents depends on their visibility and user-friendliness. It is absolutely crucial that they are introduced and studied at the earliest stages of the security sector career with regular refreshment and integrity training sessions provided to all security sector personnel.

Some of the key components of the Code of Conduct, as described by TI in their multi-country study, are listed below:

BRIBERY: Clear explanation of what is considered bribery and instructions for how to act and who to contact if offered a bribe; procedures for official reports on bribery to be investigated and procedures for notifying external prosecutors.

GIFTS AND HOSPITALITY: Clear definition of acceptable gifts and rules for their acceptance; practical guidance with real-life examples; clear procedures for officials when confronted with an ethical dilemma; readily identifiable chain of command; procedures for proper disposal of gifts.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: Clear guidance for officials to judge whether a conflict exists; procedures to disclose potential conflicts; procedures to resolve conflicts of interest.

POST-SEPARATION REQUIREMENTS: Obligation to request a formal permission from previous employer to accept offers of employment elsewhere (during 2-5 years); exclusion of gifts not related to official employment received from prohibited sources (for 2 years after leaving); reporting of such gifts.[3]

The success of the Codes of Conduct also depends on the mechanisms for reporting and consulting that are in place, the general approach to the importance of ethical behaviour within the establishment, and the importance of flagging improper behaviour. As OECD points out, effective internal controls, ethics, and compliance programmes should be in place, as well as a clearly articulated and visible policy prohibiting unethical behaviour. This must be accompanied by a strong, explicit, and visible support and commitment from senior management.[4]

Who is involved?

Codes of conduct in the security sector should be developed and implemented by the security sector establishment (Ministry of Defence, Armed Forces, Police, Border guards, and other security sector agencies as well as public and private companies that work for and with the security sector establishment, etc.). They should take into account local contexts and draw on national and international best practices and standards. They should be introduced at all levels of the security sector hierarchy and be extended to all the businesses, companies, and suppliers latter deals with.

“Ethical Values” list source: Transparency International, Building Integrity and Reducing Corruption Risk in Defence Establishments. 2009.p 17 Second edition available here.

Resources

Centre for Integrity in the Defence Sector. Criteria for good governance in the defence sector. International standards and principles (2015)

Centre for Integrity in the Defence Sector. Integrity Action Plan. A handbook for practitioners in defence establishments (2014)

Centre for Integrity in the Defence Sector: Guides to Good Governance

CIDS (2015) Guides to Good Governance: Professionalism and integrity in the public service. No 1.

Council of Europe, 1999, Criminal Law Convention on Corruption.

Council of Europe, Convention on Laundering, Search, Seizure and Confiscation of the Proceeds from Crime and on the financing of Terrorism.

Council of Europe, Convention on Laundering, Search, Seizure and Confiscation of the Proceeds from Crime.

Council of Europe, Recommendation No. R. (2000) 10 Model Code of Conduct for Public Officials

DCAF (2015), Parliamentary Brief: Building integrity in Defence.

DCAF – UNDP (2008) Public Oversight of the Security Sector. A Handbook for civil society organizations.

DCAF (2012), Ombuds Institutions for the Armed Forces: a Handbook.

DCAF Project: Ombuds Institutions for Armed Forces, List of publications.

IMF (2007) Code of Good Practices on fiscal transparency

NATO-DCAF, (2010). Building Integrity and Reducing Corruption in Defence. A Compendium of Best Practices.

NATO (2012) Building Integrity Programme

NATO (2015), Building Integrity Course Catalogue.

OSCE Code of Conduct on Politico- Military Aspects of Security

OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions.

Royal Norwegian Ministry of Defence (2011) Ethical guidelines for contact with business and industry in the defence sector.

Transparency International (2012). Building Integrity and Countering Corruption In Defence and Security. 20 Practical Reforms.

Transparency International (2012), Handbook on Building Integrity and Countering Corruption in Defence and Security. Second Edition.

Transparency International, (2011) Codes of Conduct in Defence Ministries and Armed Forces. What makes a good code of conduct? A multi-country study.

UNDP-DCAF (2007) Monitoring and Investigating the security sector.

United Nations General Assembly Resolution A/RES/51/59, 28 January 1997, UN International Code of Conduct for Public Officials.

UN Office on Drugs and Crime, United Nations Convention against Corruption.

[1] NATO-DCAF, (2010). Building Integrity and Reducing Corruption in Defence. A Compendium of Best Practices.

[2] Transparency International, (2011) Codes of Conduct in Defence Ministries and Armed Forces. What makes a good code of conduct? A multi-country study.

[3] Ibid, Template of Good Practice p 6.

[4] See Annex II: Good practice guidance on internal controls, ethics, and compliance. In OECD, Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions, 2011. p 30.