Acquisition is the process by which equipment and services sourced from external agencies are used in the building of effective military and security capability. Acquisition is a broad concept that covers the entire cycle of defence and security provision, from strategic assessment of requirements and available solutions, contracting, procurement, payments, down to evaluation of outcomes and improvement of the acquisition process.[1]

What is Acquisition Management?

The US Naval War College defines acquisition as the task of acquiring quality products that satisfy user needs with measurable improvements to mission accomplishment and operational support, in a timely manner, and at a fair and reasonable price.[2]

Ultimately, acquisition management is the process of adding new or enhancing already-existing defence and security capabilities, particularly when that process involves the introduction of new technologies. Acquisition sources are defence industry suppliers from whom the required equipment and services are procured through contractual agreements. Equipment can be weapons and other military materiel and other non-military materiel such as office equipment or defence and security infrastructure. Services are non-physical items, such as consultancy, logistic support, training and education. Acquisition involves the entire life-cycle from identification of security and defence needs through to disposal. That is, it includes identifying required equipment and services, procuring them, ensuring their support throughout their useful life-cycle and providing for their eventual disposal.[3]

Why is it important?

Decisions about equipment and services in defence involve substantial taxpayer funds and the added pressure of expected optimal performance. They also require strategic vision as to the lifespan and utility of acquired goods and services in a security environment that is always changing. Technological evolution is a factor of outmost importance in modern warfare. In this scenario, keeping defence and security capabilities of the state up-to-date has become more and more challenging and resource-consuming. Decisions about what equipment should be acquired, how long it will last in terms of various life cycles, in what time frame it will be rendered obsolete by technological advances, how to maintain the material in an optimal state, at what cost, and whether the material will produce the expected outcomes; all of these factors must be taken into account during the acquisition cycle. The same principles also apply for the acquisition of services. Overall, the need to spend scarce financial resources effectively determines a process that must ultimately result in the development of the required defence capabilities.

Acquisition is a critical area of work for building integrity efforts and anti-corruption measures. In order to ensure good governance in the security sector, it is vital that external sources contracted by the security sector abide by the same principles and the entire process is transparent and accountable.

How does it work?

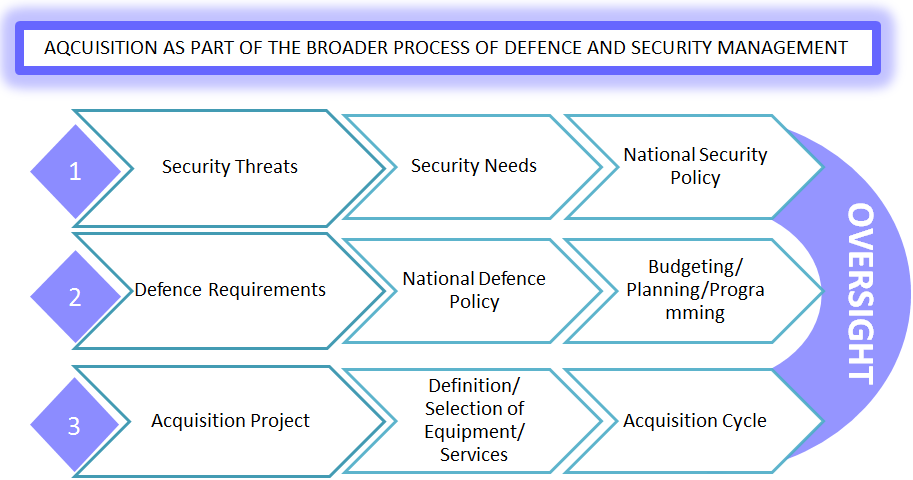

Acquisition can be broken down into three main areas of activity:

- Deciding what to acquire

- How to acquire it

- The acquisition process itself[4]

Deciding what to acquire is probably the most important step of the process. In order to come up with a balanced and comprehensive defence and security programme, defence and security requirements should be carefully analysed and acquisition projects prioritised accordingly. A framework of reference for this task can be found in policy documents. However, the guidance that these papers offer is often elementary. Therefore, extra analytical effort should be put into this planning process in order to find the best ways to match changing security requirements with optimal defence capabilities within the corresponding defence and security budget. Capability-based defence and security planning is a good approach to determine what services and equipment are required to attain desired capability. Establishing a description of desired capabilities facilitates the decision on what product or service to acquire. Defence and security planners should take into account the following factors affecting capability:

- Possible defence and security policy changes

- Threat and security environment changes

- Technological development and modernisation

- Doctrine changes[5]

Deciding how to acquire equipment and services is usually achieved through the preparation of an acquisition strategy, a formal document that records and justifies the decisions taken. One of the objectives of an acquisition strategy is to consider a wide range of possible acquisition options and to justify the specific route that is chosen as a result. An acquisition strategy also provides a reference document for the duration of the project. Additionally, the document serves as evidence for oversight and scrutiny. Therefore, acquisition strategies should be considered living documents as they will undergo continuous evaluation and improvement.

Some of the questions that should be considered at this stage:

- Does new equipment need to be procured?

- Is the equipment/service available off-the-shelf, or does it need to be developed?

- What is the scope of the acquisition?

- Are the required equipment and/or services available from more than one supplier?

- Are other states interested in a similar acquisition project?

- Does the capability need to be acquired in one go?

- How will the project be structured?

- Who will manage the project?

- How will the supplier be paid?

- How will the maintenance of the equipment be organized?

- What are the risks of a particular project how will they be handled?

- Is the equipment/services provider selected on the basis of a fair and transparent competition?[6]

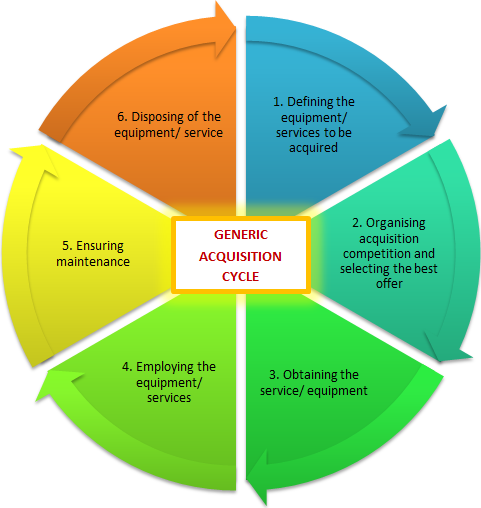

The act of acquiring equipment or services, the maintenance of equipment, and its ultimate disposal is a process lengthy and complex process that can be broken down into several stages. These stages make up a cycle known as ‘the acquisition cycle’. Acquisition cycles provide a structure to manage the acquisition process form the initiation of the project through to the final disposal of project equipment or termination of project services. Thus the cycle is a management framework. Each project will have its own specific acquisition cycle, composed of small stages covering the entire lifespan of the project and allow for flexibility in handling arising challenges and adapting to changing circumstances.[7]

Who is involved?

Acquisition involves various disciplines and skills. There are broadly four categories of stakeholders involved: decision-makers and planners, acquisition specialists, stakeholders responsible for oversight, and external agencies. Decision-makers and planners decide what equipment and services are required to cover defence and security needs. In this phase, a multitude of actors intervene, including representatives of the armed forces and security agencies who provide their expertise on technical matters. It is important to dedicate careful consideration to this planning phase as it is the perfect moment for building integrity measures. Acquisition specialists will, usually, be responsible for managing the bulk of the acquisition project: specifying the detailed requirement, contracting with suppliers, ensuring delivery of the required equipment or services, managing through-life support and arranging for final disposal. Members of the security sector senior leadership oversee and scrutinise acquisition projects. Additionally, at the programme level, there is a need for independent oversight of the overall process. Finally, external agencies are those that have the means to supply services and equipment to the security sector.[8]

Resources

Centre for Integrity in the Defence Sector. Criteria for Good Governance in the Defence Sector. International Standards and Principles (2015)

DCAF (2008) National Security Policy, Backgrounder. See new series here.

DCAF (2006) Parliament’s Role in Defence Budgeting. DCAF Backgrounder. See new series here.

DCAF (2006) Parliament’s Role in Defence Procurement. Backgrounder. See new series here.

Hari Bucur-Marcu, Philipp Fluri, Todor Tagarev (eds.) Defence Management: An Introduction. Security and Defence Management Series No. 1. DCAF (2009).

McConville Teri, Holmes Richard (eds.), Defence Management in Uncertain Times. Cranfield Defence Management Series Number 3. Routledge 2011.

McGuffog Tom (2011), “Improving value and certainty in defence procurement”, Public Money & Management, 31:6, 427-432

NATO-DCAF, (2010). Building Integrity and Reducing Corruption in Defence. A Compendium of Best Practices.

OECD (2002) Best Practices for Budget Transparency.

Transparency International (2011). Building Integrity and Countering Corruption In Defence and Security. 20 Practical Reforms.

Tysseland E. Bernt, “Life cycle cost based procurement decisions. A case study of Norwegian Defence Procurement Projects” International Journal of Project Management, 26, 2008. 366-375.

United Nations SSR Task Force, Security Sector Reform Integrated Technical Guidance Notes. 2012.

US Naval War College, Commander Raymond E Sullivan Jr., (ed) Resource Allocation: The formal process. July 2002.

[1] “Acquisition Management”, Anthony Lawrence in Hari Bucur-Marcu, Philipp Fluri, Todor Tagarev (eds.) Defence Management: An Introduction. Security and Defence Management Series No1. DCAF (2009) p 155.

[2] Source: DoD directive, cited in: US Naval War College, Commander Raymond E Sullivan Jr., (ed) Resource Allocation: The Formal Process. July 2002. p 51.

[3] “Acquisition Management”, Anthony Lawrence in Hari Bucur-Marcu, Philipp Fluri, Todor Tagarev (eds.) Defence Management: An Introduction. Security and Defence Management Series No. 1. DCAF (2009) p 156.

[4] Anthony Lawrence, “Acquisition Management”, in Hari Bucur-Marcu, Philipp Fluri, Todor Tagarev (eds.) Defence Management: An Introduction. p 156.

[5] Ibid. p. 156-175.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid. p. 177-181.

[8] Ibid. p. 157-159.